The Feedback Behind the Feedback

Feedback is an integral part of any big project. Ideally, we solicit feedback from functional experts, neutrally review their notes, and integrate their applicable suggestions. In practice, however, we often solicit feedback from our friends, review their notes somewhat defensively, and search in vain for usable insights.

Feedback is always helpful, but it’s not always helpful in the ways we expect. Though we typically use feedback as a tool for finding solutions to our project’s problems, it’s more effective (and more reliable) to use feedback as a tool for verifying our project’s problems (and determining which of them require our attention).

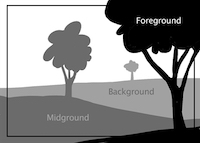

We do this by looking for the feedback behind the feedback. Readers’ suggestions are often motivated by the emotional friction they experienced when encountering our project. When we look in the background, to the feedback behind their feedback, we can identify this friction and deduce the problems that generated it.

Let’s take a comparative look. Here, a list of solutions from a reader of a working draft:

- Consider taking out chapter 3–it doesn’t seem to fit.

- Chapters 8 and 9 seem a bit long and meandering–consider combining them into one chapter.

- Some chapters start with stories and others don’t–consider using the same structure for every chapter.

- There are so many citations–I’m not sure where your argument begins or ends.

- The story in the conclusion is very interesting–move it up.

- The chapter examples are repetitive–consider mixing it up more.

These might be helpful, but they might be arbitrary. Is deleting chapter 3 a good solution? It’s hard to say when we haven’t identified the problem beyond “fit.”

If we look behind the feedback, though, we find more generative feelings:

- I’m confused, and I’m not exactly sure why. Chapter 3 seems confusing.

- I’m confused. Maybe it’s because some chapters have different forms than others.

- I’m confused. Maybe it’s because there are a lot of interruptions in the sentences.

- I’m having a hard time following this argument. I’m confused.

- I’m not interested in this argument until it’s too late. / If I’m totally honest, I find this a little boring.

What’s the friction motivating our reader? Confusion and, potentially, boredom: They can’t find the argument’s throughline. They don’t find the argument interesting. They may not find the argument relevant.

The feedback behind the feedback can feel harsh (which is why readers don’t offer it and writers don’t seek it out), but it points the way to the underlying issues keeping our project from completion. Sometimes, useful solutions are in there, but in the background. We need to look behind the feedback to find them.