It’s hard to hear no. It’s hard when the stakes are low–like when your neighborhood restaurant is out of your favorite dish, when you can’t get an appointment on your one day off, or when your child refuses to eat what you thought was their favorite dish.

It’s a lot harder when the stakes are high. Our health, our loved ones, our jobs: On these subjects, a no can unmoor us–emotionally and practically–from our sense of security, or even from our sense of ourselves.

Recently, an unmoored author wanted to better understand what motivated the collective no she’d received. She’d pitched a manuscript on an important subject with which she had deeply personal experience. Confused by repeated rejections and conflicting feedback, she wanted to know the real reasons behind the no: Was it the quality of her writing? The organization? Was the no motivated by something more personal?

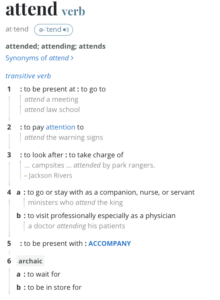

Naturally, it’s a lot easier to receive a no when it’s given alongside a good–as in, sensible, rational–reason. Logic can (sometimes) keep us from spinning our more emotionally driven wheels. Publishers don’t usually have the time to supply a good reason. But I sometimes can.

In my experience, almost every no is impersonal. Indeed, this is part of the pain we experience upon hearing it. A manuscript, even if it isn’t explicitly based on life experience, is always abstractly informed by our–very personal–life experience.

Rejections fail to recognize this because they’re typically the result of larger mismatch–between an ms and timing; between an ms and a publisher’s acquisitions or marketing priorities; between an ms and available personnel; between an ms and money.

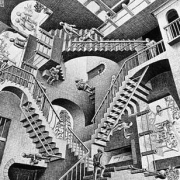

Writing and organization, regardless of their strengths, can’t usually overcome these kinds of mismatches. Then, too, a word like “mismatch”–or more often, “misalignment”–is a fluid word that can be hard to practically define. It’s a the-vibes-are-off sentiment, which may explain why authors often receive different, conflicting reasons for rejections.

Writers can’t always reposition their work to overcome misalignment. However, it can be useful to put aside a project after receiving numerous rejections, at least temporarily. We often need distance to draw useful insight from conflicting information. Further, not all nos are forever. Sometimes, as Harvard Professor Frances Frei points out, no simply means not yet.