The best books depend on a team effort.

The best books depend on a team effort.

This is not to say that a book idea should be divided up and conquered by a team of writers (although that works, too); it’s to say that generating ideas, finding good and helpful feedback, procuring specialized editing services, designing engaging interiors and exteriors, creating solid marketing plans, and more depend on a team of specialists.

Among these specialists, a publicist or PR rep is invaluable.

For some authors, a publicist feels unnecessary: Isn’t the author the person best positioned to sell their book? Aren’t they most capable of speaking (and loudly) to its merits? For other authors, a publicist feels extraneous: Why should an author pay someone else to market a book that’s already great?

But regardless of an author’s intent or a book’s brilliance, selling a book is hard work. It requires a plan for priorities and scope, a deep(ish) list of relevant contacts, and attention to small and large details over the long term.

An author can often meet many of these criterion, but they’re almost always better positioned to do so with the help of a good publicist.

A good publicist will mean different things to different authors. But in general, a good publicist has broad experience in the author’s genre. Because of that, a good publicist also has a list of contacts in relevant media industries and with outlets where their authors will benefit from coverage. A good publicist is familiar with media lead lists and is comfortable engaging in a variety of ways on social media. A good publicist works with authors to ensure authors articulate their goals, are best positioned to meet those goals, and are able to recognize—and celebrate—when those goals are met.

Publicists are an investment, and that, coupled with the sense that they aren’t really necessary for good books, means that they’re often overlooked. But smart authors know they can best sell a book the same way they wrote it: with the help of a team.

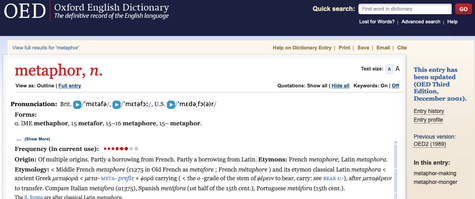

In The Moves that Matter: A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life (slated for November release), Jonathan Rowson calls chess a meta-metaphor. He means that chess—in its constrained freedom, broad competition, and negotiated relationships—provides a library of comparisons to help us think deeply about life. But Rowson also claims that there’s a sense in which the metaphor of chess “has greater reality and resonance than the game itself” (13).

Rowson’s point deserves unpacking, which he capably does in his book, but it’s his identification of a metaphor’s practical power that matters here.

In etymological terms, metaphor breaks apart into meta-, for change, and phor, for carrying. It’s typically consigned to the literary, but it’s used powerfully (also pitiably) in public and political discourses—think of Trump’s expedient invocation of a “witch hunt” or his specious claim to “drain the swamp.”

While politicians know that well-chosen metaphors influence people’s opinions, research confirms that metaphors change behaviors, too. In the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, researchers present a study focused on the continuation of preferred behaviors after goal completion. What, for example, helps people continue eating healthfully after completing a diet program? Or, what helps college students

keep at their study habits after they’ve aced the test? What did researchers find? The metaphor matters. Participants who considered their attainment of a goal as part of “journey” were more likely to continue the behaviors that brought about achievement. The two other participant groups—one of which considered goal attainment a “destination,” and one of which applied no metaphor at all —demonstrated no such likelihood of continuing preferred behaviors.

While metaphors will almost always add panache to your work—be it a speech, an article, or a book—it turns out that they also help us reflect on our lives and, according to recent research, live better ones.

Last week, I mentioned the important communications processes that help keep tech writing projects running smoothly. This week, I want to reiterate their importance by rationalizing their use.

Last week, I mentioned the important communications processes that help keep tech writing projects running smoothly. This week, I want to reiterate their importance by rationalizing their use.

For most project participants (and general readers, too), communications processes are basic logistics management: They’re in the background, they’re boring, and they feel inconsequential.

However, if you’ve worked on a tech writing team (or any writing team), you know that projects often fall (gently or painfully) apart. Project managers forget to reply-all; SMEs miss their interviews; writers edit old versions; proofreaders fail to update and send out style guides.

Most of the time, the problems can be traced back to ineffective communications processes.

A successfully completed multimember team project (where “success” equals an excellent product and the mutual respect and good will of team members), requires a project lead, weekly team meetings, uniform file-naming system, and general team investment in the efficacy of the communications processes.

An identifiable and self-identified project lead updates everyone and holds everyone accountable. Without a recognizable lead, it’s hard to identify a “team,” and a project may not even get off the ground.

Weekly team meetings that are written into the project calendar make the project an obvious priority. Ad hoc meetings theoretically work, but the work calendar self-populates at a rigorous rate, and it’s almost always impossible—especially with far-flung team members—to schedule a meeting tomorrow that everyone can attend.

The utility of a rigorously used file-naming system is obvious. But it requires use and enforcement. If a project lead doesn’t establish and apply it, a file’s dead versions are resurrected and important updates get lost.

Boring? Maybe. But most definitely consequential. If you work on writing projects (or aspire to), do yourself a favor by establishing the communications processes that will make your project a success.

Partly because they’re team-based, partly because they’re

Partly because they’re team-based, partly because they’re

produced over an extended period of time, and partly because production is iterative, tech writing projects require rock-solid communications processes to ensure completion.

Communications processes refer to the ways that team members provide reviews, comments, revisions, approvals, and updates. Sounds (somewhat) simple, but a typical white paper often includes a client, a project lead, one or two writers, two or three subject-matter experts, and an SME liaison (sometimes affectionately called the “wrangler”). This 7- or 8-person team may start their project on the same page, but when a file is misnamed or misplaced, or an SME interview is missed or mis-scheduled, the project can easily run off track.

Wayward writing projects stretch scope, but they also stretch the patience of participants, which can be even more frustrating.

To help mitigate mishaps associated with files or individual schedules (because they can never be completely avoided), establish a sound communications process while setting the project scope. This means:

- Making the project lead the communication lead

- Building weekly team meetings into the project calendar

- Creating a file-naming system to enable quick and easy referencing

- Adhering to set schedules (and processes)

Next-level communications processes include ensuring team members cc the communication lead on all emails, putting Zoom or other conferencing info numbers and links in all project-specific emails, and sending out a weekly project calendar with relevant updates.

Implementing and practicing effective communications processes can be arduous, but by helping to navigate the pitfalls that throw projects off track, rock-solid communications ease the load and lead to quicker completion.

If you’ve ever looked to produce a yearly report, a white paper, a series of tech sheets, or any other project that falls under the broad and rather complicated category of “tech writing,” you’ve probably felt overwhelmed and unsure about where to start. This post can help.

Approaching and efficiently delivering any tech writing project is a big job. However, it’s a job worth learning more about because it can encompass many different projects, can be enormously beneficial across a range of business, and can resonate with a variety of audiences.

In this post, I’ll discuss some of the best approaches to effective and efficient tech writing. In posts to follow, I’ll identify useful tools to aid execution and completion.

Starting and finishing tech writing projects depends on setting scope, communicating progress, soliciting feedback, and submitting or publishing the final work.

Setting a rigorous scope constitutes the first step, and it is key. When you set a scope for a tech writing project, you determine:

- Marketing objectives

- Topic and style

- Content team

- Calendar and schedule

Although tech writing projects are built to suit, with a prefigured topic and audience, it’s still important to explicitly identify every project’s topic and readership.

The identification is necessary because most tech writing projects are produced by a team, often with an outside writer. Ensuring that every team member knows what they’re writing about (and for whom) ensures consistency. It also helps project leads get as specific as possible about their marketing objectives: After all, a tech-based Q&A offered as a download on a business’s website reaches a different audience than the same content published through a trade organization.

Setting scope also requires identifying subject matter experts (SMEs) who can contribute objective and evidence-based material. Designating SMEs before a project begins—and often bringing them into the process of setting scope—can gain their timely and invested participation.

Finally, setting scope requires a calendar and schedule. There’s really no way around the fact that tech writing is an iterative process, and each iteration requires review. Identifying the team and gaining their early buy-in can help manage touchpoint fatigue (aka, “You need me to look at this again?”). Creating a granular schedule can ensure maximum efficiency. When SMEs and others can anticipate the commitment required from the jump, they can better rise to their role.

Setting scope is the most important step in completing tech writing projects. Sharing the scope ensures that objectives are met, that SMEs understand and anticipate their commitment, and that the project moves along as efficiently as possible.

Inspired by my last post’s gif and by a few recent client experiences, I want today to advocate for the phone.

For contract workers, freelancers, and anyone working remotely, email (and its more casual cousins, like Slack) are the queens of communications processes. Asking a quick Q, updating a far-flung project partner, onboarding a client: In all of these cases (and most others) it feels supremely efficient to send a quick email. Email lets you get stuff done when you’re in the midst of other work.

But sometimes that’s a problem. Email aids the multitasker, but its benefits are often perceived rather than real (research typically shows that the high mental cost of task-switching makesmultitasking pretty inefficient anyway).

At the same time, inbox scope creep is very real and a very real problem. It’s hard to hierarchize replies and responses to anything when everything—every query, question, and fyi—is piled on top of an already towering heap.

Meanwhile, the phone, also a tool of communication, seldom feels like an appealing alternative. In the email era, a call may feel a little intimidating. It’s more involved, and it’s more intimate, perhaps because it seems to require participants’ (almost) complete attention.

But a phone call conveys care, and—because it assumes an immediate response—helps aid prioritization. It can also keep projects running smoothly. A few years ago, I began integrating phone calls into my SOP where I’d typically send an email. It’s hard to gauge the impact on productivity, but I absolutely noticed a difference in my work. Getting on the phone to more regularly check in and troubleshoot helped partnerships feel real and invested.

Because of this, I’ve become an advocate for picking up the phone: It may be out of style, and it definitely feels more labor intensive, but that doesn’t mean it’s not time to bring it back.