Revision: The Sum of Subtraction

While some writers approach revision as a set of fun problems to solve, most approach it as a set of high-stakes, anxiety-producing riddles.

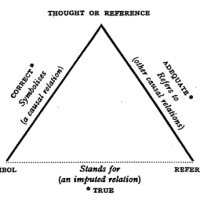

Revision, like all writing, requires both thinking and doing, or, in John Warner’s more evocative words, “expression and exploration.” Because we tend to subtract when we think, but add when we act, the work of writing is particularly difficult. To write–and revise–well, we must strategically wield apparently opposed forces.

Our subtractive thinking is represented by heuristics, those mental shortcuts that slice through the abundant inputs we take in every second of every hour of every day that we’re alive and awake. Heuristics subtract; they help us move from the potential paralysis of contemplation to the decisive movement of action (while also abetting our many and diverse biases).

Meanwhile, our actions, particularly when directed toward object transformation, are frequently biased toward addition. In the linked study, participants were asked to change a Lego structure to make it more stable. Most participants, unless explicitly cued with directions to “streamline” their structure, added to it. They only rarely used subtractive strategies, though those typically yielded greater stability, and were more efficient.

If (to adopt a gritty heuristic), we subtract when we think and add when we act, how should we handle the work of writing and revision?

Primarily, we should separate the work into separate processes. Writing and revision both mean doing transformative thinking, but addition and subtraction serve each activity differently. Writing is all about adding–if we prioritize subtractive thinking and heuristics, we risk subtracting meaning.

Revision, however, should be understood as an implicit directive to “streamline” the object of our thinking. We practice efficient revision when we apply our subtractive powers to the writing we wish to transform.

Ultimately, when facing the challenge of revision, we may need to subvert our instinct to add more to stabilize our work. We should first consider the sum of subtraction. Subtractive revision makes the additive force in/of further action possible. Once we’ve taken out the extras, we can see what else should be included.