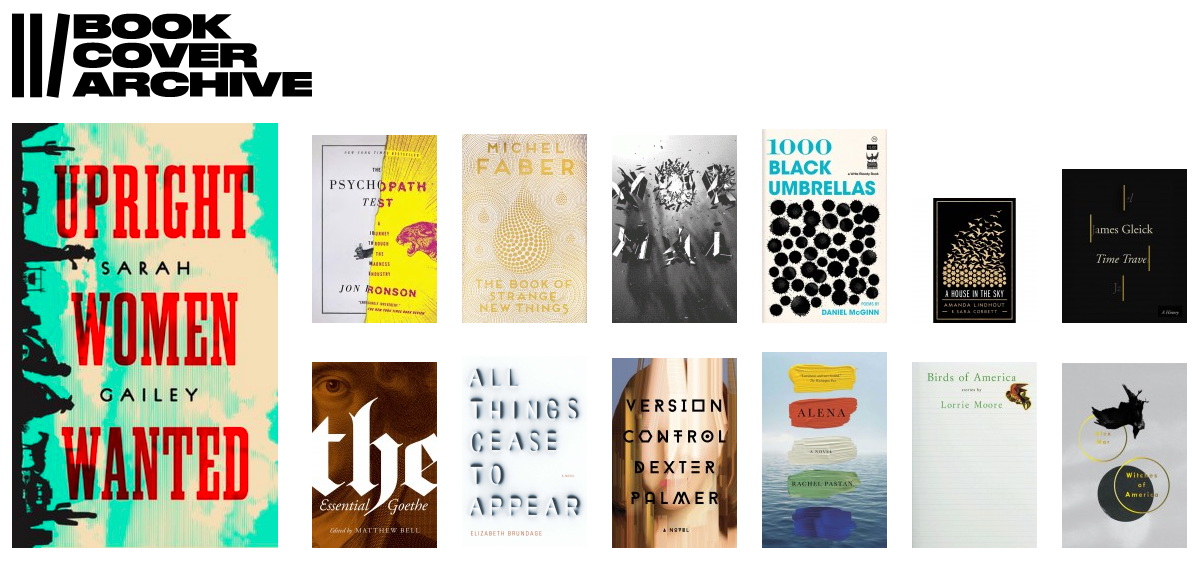

This post it not a how-to. No primer, no matter how comprehensive, can teach the know-it-when-you-see-it quality that catapults an everyday shelf-piece into the realm of book art.

The Peter Mendelsund-designed Ulysses (as well as Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), provides a startlingly effective illustration. Here is style and savvy in spades. But here, too, is the kind of entrainment between writer, reader, and designer that channels a book’s essence.

In The Wave and the Mind, Ursula Le Guin describes entrainment as the tendency for two wall-mounted clock pendulums to slowly swing in sync. Physicists call this “mutual phase-locking”; Le Guin describes it as the “beautiful economical laziness” by which successful relationships are formed.

It’s all a little spectral, but this (2013) Ulysses cover illustrates the certain quiescence by which a design imparts the spirit of a story. What looks like boldly scribbled marginalia interrupts but also completes the title with the “yes” acknowledging the book’s last—and now first—word and its (arguably) most famous line: “yes I said yes I will Yes.”

While this isn’t a how-to, it does offer an injunction: When approaching book cover design, find inspiration in books that illustrate style, savvy, and this kind of economical soul. Then, aim that high.

The best books depend on a team effort.

The best books depend on a team effort.

This is not to say that a book idea should be divided up and conquered by a team of writers (although that works, too); it’s to say that generating ideas, finding good and helpful feedback, procuring specialized editing services, designing engaging interiors and exteriors, creating solid marketing plans, and more depend on a team of specialists.

Among these specialists, a publicist or PR rep is invaluable.

For some authors, a publicist feels unnecessary: Isn’t the author the person best positioned to sell their book? Aren’t they most capable of speaking (and loudly) to its merits? For other authors, a publicist feels extraneous: Why should an author pay someone else to market a book that’s already great?

But regardless of an author’s intent or a book’s brilliance, selling a book is hard work. It requires a plan for priorities and scope, a deep(ish) list of relevant contacts, and attention to small and large details over the long term.

An author can often meet many of these criterion, but they’re almost always better positioned to do so with the help of a good publicist.

A good publicist will mean different things to different authors. But in general, a good publicist has broad experience in the author’s genre. Because of that, a good publicist also has a list of contacts in relevant media industries and with outlets where their authors will benefit from coverage. A good publicist is familiar with media lead lists and is comfortable engaging in a variety of ways on social media. A good publicist works with authors to ensure authors articulate their goals, are best positioned to meet those goals, and are able to recognize—and celebrate—when those goals are met.

Publicists are an investment, and that, coupled with the sense that they aren’t really necessary for good books, means that they’re often overlooked. But smart authors know they can best sell a book the same way they wrote it: with the help of a team.

When facing a discussion that may feel intimidating or adversarial (for me, this is typically an interventional phone call for a fragile or otherwise off-track project), “intimidating” can stand, but “adversarial” must be recast.

Feeling intimidated, or what Mallory Pickett calls feeling the fear, can be an excellent exercise in humility. The Antidote persuasively argues that getting comfortable with this kind of discomfort is an important and worthwhile skill. It doesn’t mean ignoring discomfort, though—quite the contrary—it means allowing discomfort to exist, allowing conversations to feel and be challenging, allowing uncomfortable silences to happen, and, ideally, allowing all points of view to emerge.

But while it’s okay to be intimidated by the prospect of a difficult conversation, it’s not productive to sustain an inner dialogue and accompanying imagery that casts the conversation as a battle in which a winner will emerge victorious after vanquishing a loser. I know when I rehearse a difficult conversation, I sometimes slip into attack-and-defense mode—but when I want to win and not lose, I’m focused not on the project but on my (single, limited) point of view.

Instead of viewing conflict as adversarial, it’s helpful to occupy the position of a science journalist who works not to win a point but to gain as much information as possible. Making information the goal takes the onus off conversational combat and helps to unify different views by refocusing them on the project.

Because gaining information is the goal, the best preparation for difficult conversations is, ultimately, preparation. This might take the form of role playing a difficult conversation, or it may take the form of research that provides insight and context for the client’s point of view, or it might take the form of breathing exercises that can provide comfort in the midst of discomfort. Science journalists take on the work of confrontational reporting because they want to fully answer a sometimes slippery question. Their techniques apply to anyone who has to talk it out.