The weekend is coming! The weekend is coming! And while that news alone is a source of joy and wonder, it’s doubly so this weekend because Saturday is Independent Bookstore Day!

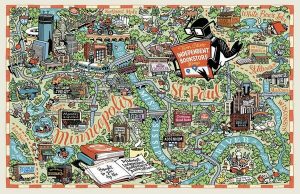

Where will you visit and what will you buy? If you’re in the Minneapolis area, you might try The Wild Rumpus for a belated copy of The Country Bunny and the Little Gold Shoes, or maybe the Red Balloon in anticipation of the newest Wings of Fire? How about Birchbark for Killers of the Flower Moon, or Once Upon a Crime for the creepy classic, Rebecca? Or maybe you’ll head to Magers and Quinn for a newer classic, The Great Believers?

Or maybe you’re working, or digging in the (muddy [snowy?]) dirt, or riding the bleachers at a child’s doubleheader. If you can’t get out and about in your neighborhood, there’s always the internet’s busy streets. Specifically, you might try Belt Publishing for the Minneapolis-superfan’s Under Purple Skies.

Buying independent is an excellent way to make manifest your belief in the restorative value of books and the invigorating power of independent bookstores.

It’s true that books are expensive and can be borrowed—for free—from the library (libraries!). But good books are forever: You read them once or twice or more. You read them aloud to those you love. You lend them to those you trust. You gush over them with acquaintances and hate on them with strangers. You revisit the phrases, the characters, the scenes, the stories—and the images and feelings they invoke—over the years of your life. And good books make those years so much better.

And bad books? They’re the worst. But even bad books deserve a second life in more appreciative hands. So sell back A Little Life and The Flamethrowers to the used bookstore, and try to remember that the books we hate also give us something to think over and question, and that’s a lot.

Find your Minnesota-specific guide to Independent Bookstore Day at Rain Taxi or Twin Cities Geek. And reserve Saturday for spending money on the booksellers, bookstores, book publishers, book printers, and, of course, the authors that entertain, educate, delight, and, sometimes, astound us.