The many responses to Marie Kondo, her book, her method, and her show are worth a read. There is something delightful about the method’s animistic approach to stuff. It feels right that every single one of our possessions should spark something—whether that’s joy, usefulness, hope…or just recognition. But, as others (and Twitter) have vociferously argued, there’s also something depressing about radically minimizing our possessions according to our current feelings. Times and feelings, perceptions of “sparks” and “joy,” change. All the time!

Whether you’re all in on KonMari mania or you’ve chosen to hold on to that double-stack tower of unread books, KonMari can be usefully applied to writing projects. While it’s the rare MS Word snippet that inherently “sparks joy,” KonMari’s emphasis on disciplined organization—decanting, disposing, and developing a daily habit—can help productively compose a jumbled Google doc.

Consider the KonMari-approved method of decanting household products into simple containers. This, argues Kondo, reduces the extraneous “noise” of packaging and frees the product to be, as designer William Morris once advised, beautiful and useful. Beginning a project by freeing it from the confines of its context—perhaps by using Webjets, Scrivener, a new doc, a legal pad, or Nabokov-approved notecards—can help you see your work in a new way, enabling you to push it in more generative directions.

Or try the KonMari argument for guilt-free disposal. Because writing can be so difficult, the material we produce often feels sacred. We might think that a great paragraph—even if it doesn’t really work—is just too good to let go. While these sentences might spark joy, their sparks are obstructive rather than clarifying. If you can, delete your fragmentary darlings with impunity. If you absolutely can’t, create a separate file for fragments. You may find a use for them yet.

KonMari also suggests developing a daily habit of cleaning out your bag. We already know that organized writing aids sleep, so when it comes to your projects, this isn’t just helpful, it’s healthy. At the end of your work, go back over what you’ve written. Determine what works and what doesn’t. File the uselessly joyful/joyfully useless fragments in a separate doc. Run spellcheck and format the page. Note what still needs to be outsourced (and sourced), and create a list of writing to-dos for the next session. Like the concept of parking your car downhill, when you make a habit of regularly tidying up your work, you position yourself for maximum momentum.

Tragically, the KonMari method is not going to transform your project into a minimalist masterpiece. Big projects will probably always require baroque amounts of blood, sweat, and tears to be magically transformative. But the KonMari method offers easy-to-execute organizing habits that can help every writer.

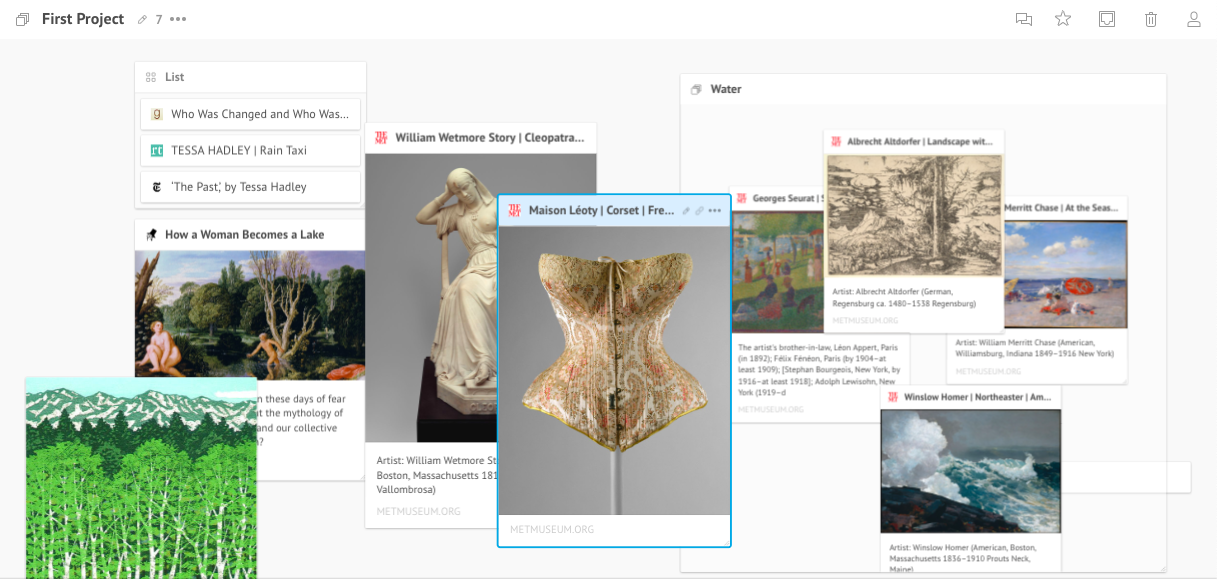

For example, if you’re working on a speech or a presentation, you could fill your canvas with thumbnail links of your subject matter. You could then attach other links (like particularly apt comments or tweets or relevant op-eds), other images (like a grabs from previous presentations), and text-based responses (like lists of audience questions) onto the images themselves.

This is helpful, and in some surprisingly deep ways. If you’re looking to repurpose or refresh a project, Webjets provides an engaging format through which to envision your work. If you’re looking to gain insights or access points into stubborn questions, Webjets can help you reorganize your files in new ways (like lists, cards, folders, or mind maps). If you’re looking to collaborate with a partner or a team, Webjets lets you share your screen for pretty efficient (and frankly very fun) collaborative brainstorming sessions.

Did I need a new way to envision and brainstorm new projects? In fact, yes! My old way of brainstorming cannot even be called a “way”; it’s certainly not efficient; and it’s not at all conducive to structured collaboration. As we work on bigger, more collaborative projects at MWS, Webjets offers a narrative snapshot that is more comprehensive and more dynamic than a linear or written description.

The question of whether or not Webjets aids productivity is harder to answer. On the one hand, it will undoubtedly add to the bottomline of time spent brainstorming and collaborating. On the other hand, if it means the end result is a smarter and more creative project, then I’ll happily take it. Have you used Webjets? Tell me more.